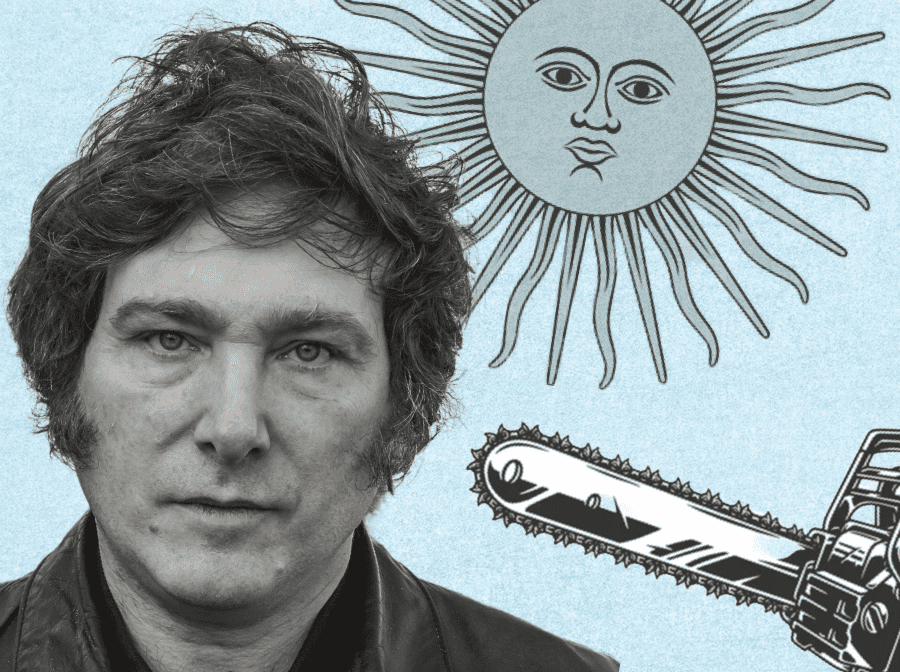

Argentina has elected a chainsaw-toting right-wing maverick with ideas that many people find economically incoherent, if not plain bizarre. Yet the wine industry dares to hope that life under Javier Milei may be less painful than what it’s endured in recent years. By Graham Holter

Argentina’s new president is a chainsaw-wielding anarcho-capitalist who reportedly consults cloned dogs for economic advice. Yet Javier Milei won a comfortable victory in the November election, with support from large sections of the country’s wine industry, despite promising economic reforms that stand a fair chance of making life even more difficult than it’s been under the Peronist regime.

Mendoza, which produces 70% of the wine in Argentina, was more enthusiastic about the far-right maverick than almost any other region. Here, Milei took 71.1% of the vote, and he also enjoyed solid endorsement from San Juan (60.6%), Neuquen (60.4%) and Salta (57.8%).

From an outside perspective – even from a continent as prone to right-wing populism as Europe – Milei’s victory looks like yet more evidence of a world gone mad. But there are solid reasons why people in the wine industry were prepared to support him.

The first thing to consider is Argentina’s almost crazily scary economic woes, with the peso tanking (and being traded at a range of exchange rates) and inflation running rampant: 140% at the time of writing. But as Lee Evans of specialist South America importer Condor Wines explains, those aren’t the only problems.

“They had the terrible frost in November 2022, going into December, and that wiped away more than 30% of the crop in some areas, and in others it was 50%,” he says.

Yet producers have still taken a hit on their export prices, recognising that the kind of inflationary increases they pass on at home would be impossible to achieve internationally.

“They hope for better things on the horizon,” Evans adds. “And in the meantime, they want to protect their export markets. OK, in Argentina they’re changing pricing every week, every day. But they can’t do that in international markets.”

Laurie Webster runs another South American specialist, Ucopia Wines.

“I’ve never, ever known a more stoic nation when it comes to that ability to bite down on their lip and hold the prices as much as they possibly can, in order not to lose market share and commercial edge, in the context of what they have to face,” he says.

“It’s really quite unbelievable that their wines are still affordable. I think our government’s done more to increase the price of Argentine wine than the Argentine government.”

The lady in the Western Union filled one and a half little backpacks with massive wads of cash. It was like we had just robbed a bank

Doing business with Argentina requires a certain amount of creativity. Privately, there are stories shared about how a percentage of a wine’s import price – typically 25% – will be diverted to a third party, perhaps in New York or Jersey. The invoice will refer to “marketing expenses” or perhaps dry goods. This arrangement allows the exporting producer to realise more value for its wines than if the entire bill was being processed through the banking system in Argentina.

Anyone from the UK wine trade who visits Argentina will quickly realise that exchange rates vary wildly. As Laurie Webster explains, there is the official rate and the so-called blue rate.

“The blue rate has always existed,” he says. “But there’s never before been such a discrepancy between the two that I’ve felt the need to buy currency on a street corner.

“However, at the moment [speaking in late November], the official rate is around 380 pesos to the dollar, and the blue rate’s about 1,000 to the dollar. When [sales director Phil Crozier] and I arrived in Argentina, we took eight $100 bills with us.

“Strictly speaking, the blue rate is illegal. But it’s sort of tolerated, to the extent that we walked into a high street Western Union and changed our eight $100 bills for pesos at 900. So almost three times the value of the official rate. The lady in the Western Union filled one and a half little backpacks with massive wads of cash. It was like Phil and I had just robbed a bank. It was crazy.

“The serious side to this is that if you’re a wine producer in Argentina, and you’re invoicing people in dollars, as they all do, they can only expect to get around 350 pesos per dollar from the central bank. So they’re being brutally ill-treated by the regime there and it’s obviously really, really bad for the economy in general.

“If you’re somebody that’s trying to export and make a living, invoicing in dollars, you’re just not making any real money.

“And nothing is keeping up with inflation. So every month, wineries are having to increase their payroll. But even if they wanted to try and keep up with inflation, it wouldn’t be possible because it’s so out of control.”

A large part of Milei’s appeal is his promise to push through free-market reforms that Argentines hope will make doing business easier.

“The previous government was incredibly controlling,” says Evans. “There were times where you couldn’t get certain bottles because wineries couldn’t import them. They weren’t allowed to import because they’d gone past their quota, and the domestic market doesn’t make those bottles.

“It’s not easy to do business in Argentina but, because of that, they’re very entrepreneurial and creative.”

Daniel Pi, one of the best-known figures in Argentina’s wine industry and chief winemaker at Trapiche, is sanguine about the recent political earthquake.

“I think that Milei’s vote is more against corruption, privilege and the political establishment than for his proposals,” he says. “He is a symbol of society’s fed-up people, especially the young generation.”

Many in the trade have noted that Milei has moderated his language, and his more extreme policy ideas, since taking office. The plan to dollarise the economy has been shelved, but the exchange rate issue still needs a solution.

“This huge spread of exchange rates makes everything very uncompetitive for the industry,” says Pi. “It makes wine artificially very expensive, and the profit very low for the entry level, so we are not competitive in entry-level wines.

“I think the future will be positive. I’m very optimistic. At the beginning it will be difficult, but in two or three years things will become more stable and hopefully people will start seeing the light at the end of the tunnel.”